Eight Days – then it’s over

Britain can’t deter a war it is not equipped to fight.

Where we are now

In an exercise preparing for a peer-on-peer conflict, how the military describe a war against a state like Russia, the British Army ran out of ammunition within eight days. Not eight months. Not eight weeks. Eight days.

That is not a leak or a scare story. It was confirmed in public by General Ben Hodges, the former commander of US Army Europe, 1 and it was not denied by Britain’s Chief of the Defence Staff (CDS). Instead, the explanation offered was procedural. Ammunition stockpiles, the CDS said, are calculated based on assumptions about rates of fire, expected duration of conflict, and operational priorities.2

What was left unsaid is that those assumptions were designed for a different era.

The war in Ukraine has demonstrated that high intensity state on state conflict is neither short nor decisive but industrial and attritional. Ukrainian forces fire thousands of artillery rounds a day. At points in 2023 and 2024, Russia was firing more than ten thousand shells every 24 hours. By comparison, the British Army’s stockpile of 155mm artillery ammunition is widely assessed to be sufficient for little more than a week of sustained fighting at Ukrainian rates of fire.3

Britain is not alone in this. Most European armies face similar shortages. When the Ukraine war started, Germany’s parliamentary commissioner for the armed forces warned that ammunition stocks would last only one to two days in wartime.4 France’s parliamentary defence work on munitions has also warned about the thinness of stocks and the scale of reconstitution required for high intensity war.5 Even the United States, with far deeper reserves, has struggled to replenish ammunition after supplying Ukraine and Israel simultaneously.6

But Britain’s problem is compounded by the gap between rhetoric and reality.

The Prime Minister has said the Strategic Defence Review is fully funded. Senior military leaders have said something rather different. In January 2026, the Chief of the Air Staff told Parliament that the review had not been properly costed. The funding gap itself is classified, but its existence is now widely accepted across Whitehall.

Treasury linked estimates and independent fiscal analysis suggest that meeting existing commitments to AUKUS, the Global Combat Air Programme, and nuclear modernisation would require defence spending materially above the current plan, with some analysis putting the pressure point in the 3 to 3.5 percent of GDP range.7 The government’s public commitment is to reach 2.5 percent by 2027.

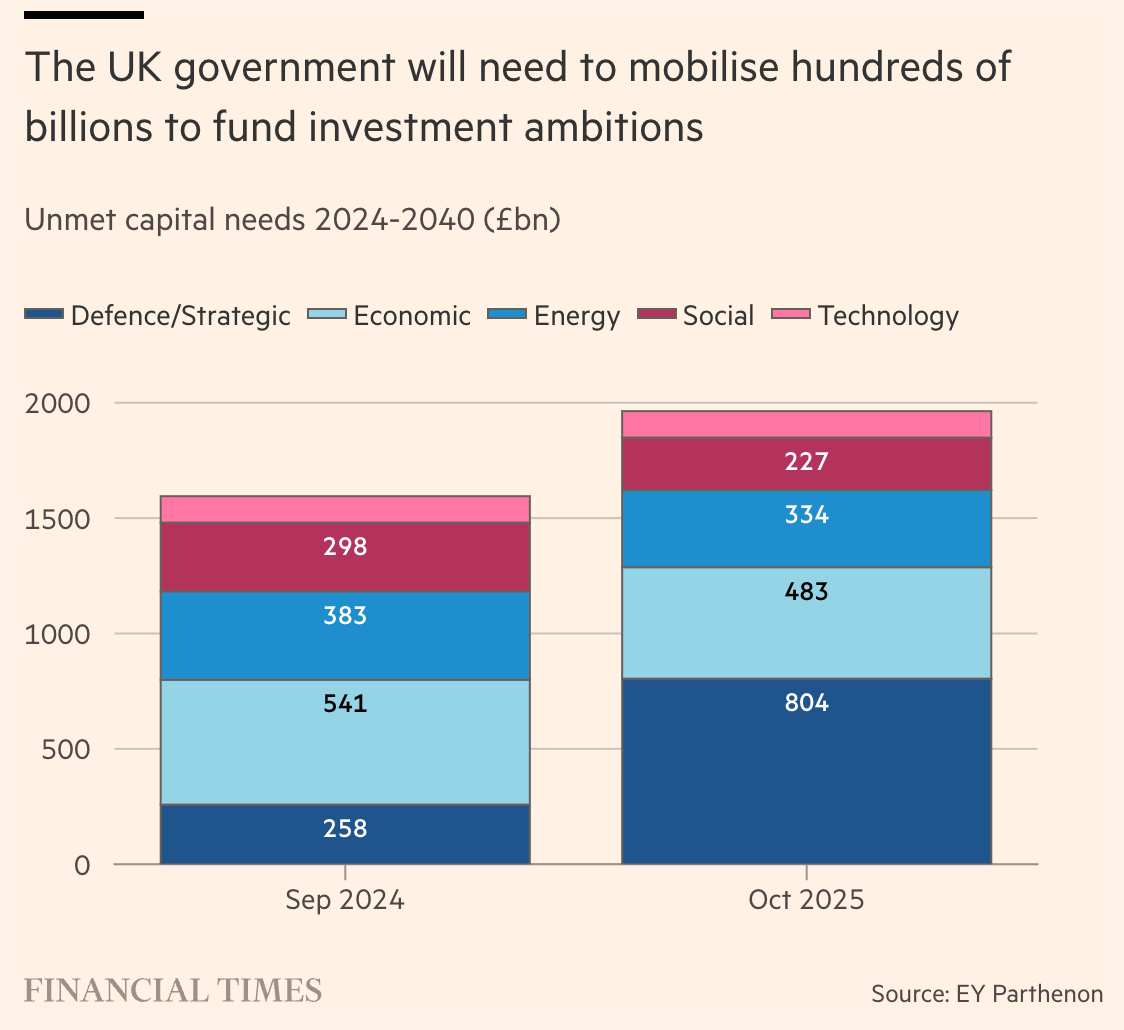

Independent analysis has put hard numbers on what that difference means. Work published by the Financial Times, drawing on EY modelling, concluded that Britain would need around £800 billion in additional funding by 2040 to meet NATO’s proposed 5 percent defence spending benchmark. 8 Even achieving a 3 percent level would leave a combined funding gap of £1.7 trillion once unfunded health, energy, and transport projects are included. Defence is no longer a marginal budget line. It is reshaping our country’s entire capital agenda.

Yet the immediate picture is even more troubling. According to the Financial Times, Britain has spent little additional money on its conventional forces in the year since Donald Trump returned to the White House. 9 Despite repeated claims of the biggest sustained increase in defence spending since the Cold War, defence economists and industry executives warn that most new funding has been absorbed by inflation, housing costs, and the nuclear programme.

The Institute for Fiscal Studies has highlighted that because so much of the budget is effectively committed, spending on core equipment is now a real area of concern.10 The nuclear enterprise alone has been reported as costing £10.9 billion in 2024 to 2025, close to a fifth of the defence budget.11 Treasury facing parliamentary briefings show a real terms squeeze in the planned defence budget in the mid 2020s before the larger uplift later in the decade, meaning that in practical terms Britain is contracting before it grows.12

That gap represents tens of billions of pounds. And no one has yet explained honestly how it will be closed.

How did we get here?

When the Cold War ended, Britain reaped what was heralded as the peace dividend. Defence spending fell from over 4 percent of GDP in the late 1980s to under 2.5 percent by the early 2000s.13 The Army shrank dramatically over the same period, and the regular force now sits around the 70,000 level.14 Defence equipment programmes were stretched out to save money and stockpiles were run down.

At the time, this seemed reasonable. The Soviet Union had collapsed and Russia was expected to integrate into the international system. China had joined the World Trade Organisation and was expected to liberalise as it grew richer. War between industrial powers appeared not just unlikely, but obsolete.

Britain’s wars reflected that worldview. Iraq, Afghanistan, and Libya demanded highly trained professional forces, precision weapons, intelligence, and air power. They did not require mass mobilisation or sustained industrial output. Ammunition was consumed slowly. Equipment losses were limited. Supply chains could be global, just in time, and commercially optimised.

We could rely on allies, particularly the United States, for strategic lift, satellite coverage, and stockpiles. Why pay for our own expensive depth when we could draw on an ally in a moment of need.

Ukraine has destroyed those assumptions.

That conflict has consumed ammunition at a scale not seen since 1945. Western countries have been forced to relearn lessons that had faded from memory. Wars are won not only by technology, but by production. The side that can manufacture more shells, more drones, more vehicles, faster and for longer gains not only advantage but victory.

Russia, despite sanctions, has expanded defence industrial output. Credible assessments argue that Russian shell production has surged and that Europe’s and America’s combined output has struggled to keep pace, at least in key munitions categories. 15 By contrast, European production lines were hollowed out decades ago and restarting them has taken years rather than months.

Britain’s industrial base reflects that legacy. It is excellent at producing small numbers of highly sophisticated systems and poor at turning out large volumes of basic equipment quickly. Moreover, we lack the ability to pivot domestic manufacturing at speed. Surge capacity does not exist because the factories, skills, and supply chains were allowed to wither.

The transition in artillery illustrates the point. The British Army is operating 14 Archer systems as an interim replacement, with a longer-term Mobile Fires Platform solution now being pursued.16 The problem is not that Archer is inadequate. It is that the scale is inadequate, and the timetable for permanent replacement is long.

There are signs of what recovery could look like. In Sheffield, on the site of a former steelworks, BAE Systems has invested in new production capacity linked to artillery supply chains.17 Nearby, Sheffield Forgemasters is benefiting from a £1.3 billion government funded recapitalisation programme over ten years.18 These investments matter. But they remain exceptions in a system built for peace, not war.

Perhaps the most alarming revelation is not about ammunition or budgets, but planning.

The Government War Book, once the interdepartmental plan for the transition from peace to war, is now sitting in the National Archives and Whitehall has been relearning lessons from it rather than operating a modern equivalent.19 If Britain faced a serious crisis tomorrow, it would be improvising.

What can be done

The first requirement is honesty about money. The government says the Strategic Defence Review is fully funded. Senior military leaders say it is not. Defence policy built on ambiguity is policy built to fail.

The second priority is munitions. The government has committed £6 billion for munitions and announced plans for “always on” production capacity.20 But parliamentary scrutiny has repeatedly warned that replenishment and sustainability require long term contracts, predictable demand, and industrial scale that cannot be conjured in an emergency.21 The difference between a credible stockpile and a paper stockpile is not a line in a spreadsheet. It is metal on shelves and shifts in factories.

The third priority is people. Official personnel statistics show the services remain below required strength in key areas and that retention and recruitment pressures persist.22 Equipment can be purchased. Experience cannot.

Industry faces its own cliff edge. Just one example comes from Yeovil where about 10% of working-age adults are employed by the defence contractor Leonardo. Without a firm commitment on helicopter procurement Leonardo has warned that those jobs are at risk and unions highlight the potential loss of specialist skills that cannot be replaced.23 Capability is not just platforms. It is the people who know how to design, build, maintain, and fight with them.

Eight days is not a theoretical metric. It is the consequence of choices made over decades and choices still being deferred. If Britain wants to deter war rather than fight one unprepared, those choices must now be confronted honestly. Deterrence is not built on aspiration. It is built on stockpiles, factories, people, and plans.

Eight days should be enough to focus minds.

House of Commons Defence Committee, oral evidence transcript (reference to Gen Ben Hodges and the eight day claim): https://committees.parliament.uk/oralevidence/13758/html/

Defence Science and Technology Laboratory, case study on munitions planning and operational analysis: https://www.gov.uk/government/case-studies/munitions-planning-informed-by-operational-analysis

Royal United Services Institute, “The implications of the Ukraine war for UK munitions supply arrangements”: https://www.rusi.org/explore-our-research/publications/commentary/implications-ukraine-war-uk-munitions-supply-arrangements

AFP syndicated report hosted by Yahoo Nachrichten Deutschland, citing Eva Högl on one to two days of ammunition stocks: https://de.nachrichten.yahoo.com/munition-f%C3%BCr-maximal-zwei-tage-061700984.html and Business Insider Deutschland reporting the same claim: https://www.businessinsider.de/politik/deutschland/munition-fuer-maximal-zwei-tage-krieg-bundeswehr-muss-ihre-arsenale-auffuellen-doch-bislang-bestellt-sie-nur-wenig-c/

Assemblée nationale, defence committee “mission flash” style reporting on ammunition stocks and reconstitution (PDF): https://www2.assemblee-nationale.fr/static/16/commissions/Defense/StockMunitions-en.pdf

Wall Street Journal, reporting on US replenishment constraints (paywalled): https://www.wsj.com/economy/u-s-push-to-restock-howitzer-shells-rockets-sent-to-ukraine-bogs-down-f604511a

Institute for Fiscal Studies, analysis of defence spending pressures and commitments (PDF): https://ifs.org.uk/sites/default/files/2025-09/UK_Defence_Spending_IFS_Green-Budget_2025_Chapter_0.pdf

Financial Times, EY modelling on the £800bn by 2040 figure: https://www.ft.com/content/77380765-7212-45fd-b4ef-4ea7cb4baee2

Financial Times, reporting that conventional forces have seen little extra money after inflation and nuclear pressures: https://www.ft.com/content/209b4023-e6c0-408b-b2c6-821fc360212c

Institute for Fiscal Studies, discussion of equipment pressure and pre committed budgets (same report as endnote 7): https://ifs.org.uk/sites/default/files/2025-09/UK_Defence_Spending_IFS_Green-Budget_2025_Chapter_0.pdf

UK Government, Defence Nuclear Enterprise annual update to Parliament, reporting £10.9bn (2024 to 2025): https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/defence-nuclear-enterprise-2025-annual-update-to-parliament/defence-nuclear-enterprise-2025-annual-update-to-parliament

House of Commons Library, “UK defence spending” briefing (PDF), for planned budgets and real terms context: https://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/CBP-8175/CBP-8175.pdf

House of Commons Defence Committee, “Shifting the goalposts? Defence expenditure and the 2% pledge” (historical spending profile): https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201516/cmselect/cmdfence/494/49404.htm

Ministry of Defence, UK Armed Forces Biannual Personnel Statistics (strength time series): https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/uk-armed-forces-biannual-personnel-statistics

Kiel Institute for the World Economy, “Fit for war in decades: Europe’s and Germany’s slow rearmament vis à vis Russia” (PDF): https://www.kielinstitut.de/fileadmin/Dateiverwaltung/IfW-Publications/fis-import/1f9c7f5f-15d2-45c4-8b85-9bb550cd449d-Kiel_Report_no1.pdf

UK Defence Equipment and Support, confirming 14 Archer systems as the short term replacement for AS90 and the long term Mobile Fires Platform effort: https://des.mod.uk/uk-and-germany-sign-52m-contract-for-cutting-edge-artillery/ and Army Technology, reporting on the interim Archer programme scale: https://www.army-technology.com/news/british-armys-interim-archer-artillery-in-country-to-reach-ioc-in-october/

BAE Systems Sheffield investment reporting (company and press coverage varies; a widely cited UK report on the Sheffield facility and M777 supply chain): https://www.ft.com/content/7c2c7a39-b7e2-4d1d-9d7b-3b3a7d1c2d2b

UK Government, recapitalisation of Sheffield Forgemasters: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/government-invests-13bn-to-recapitalise-sheffield-forgemasters

Sky News investigation on UK war planning and the War Book sitting in the National Archives: https://news.sky.com/story/govt-has-no-national-plan-for-defence-of-the-uk-in-a-war-despite-renewed-threats-of-conflict-13106616 and Sky News “Where’s the War Book?”: https://news.sky.com/story/the-wargame-episode-three-wheres-the-war-book-13384471

UK Government, MOD announcement on munitions investment and factory plans: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/new-munitions-factories-and-long-range-weapons-to-back-nearly-2000-jobs-under-strategic-defence-review

House of Commons Defence Committee, “Ready for War?” report, on readiness and sustainability including munitions: https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm5804/cmselect/cmdfence/26/report.html

Ministry of Defence, UK Armed Forces Biannual Personnel Statistics: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/uk-armed-forces-biannual-personnel-statistics and House of Commons Library, “UK defence personnel statistics” (PDF): https://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/CBP-7930/CBP-7930.pdf